Philip Mayo cost himself a law enforcement career the day he helped shatter a prison inmate’s face and beat him until his back was broken.

But the fired Maryland corrections officer wasn’t out of uniform for long.

Within months, G4S, the largest private security company in the world, gave him a job 20 minutes up the road guarding an office building and its workers.

Co-workers said he raised more red flags almost immediately. They claimed he stalked a woman around the building. He adjusted security cameras to watch women enter the locker room. He groped a coworker’s breast.

Mayo’s supervisor warned his bosses: Fire this guy before someone else gets hurt. They ignored him.

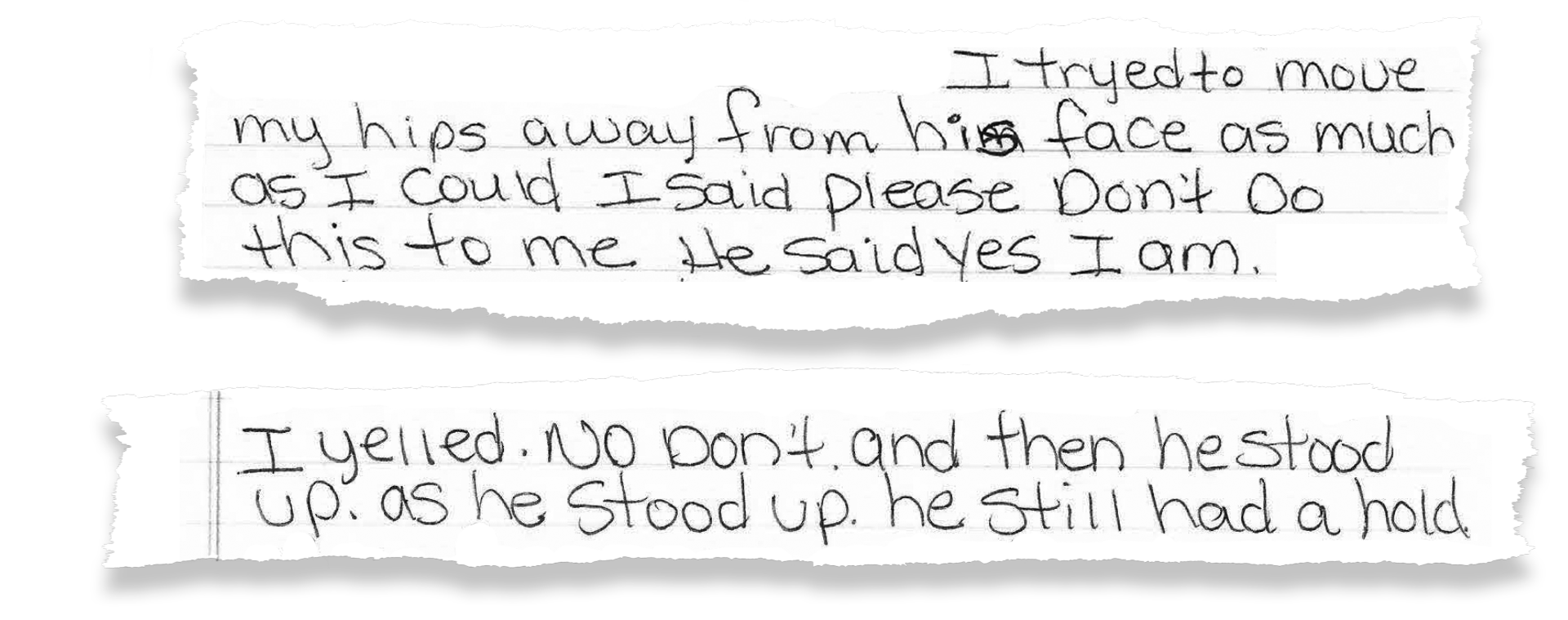

A police report details what happened next. One night on the graveyard shift, Mayo watched a cleaning lady push her cart down a darkened hallway. He waited until they were alone.

Then he pinned her from behind, slammed her head against the wall and ripped at her clothes. “Please don’t do this,” she begged.

"I do what I want,” he said. "I’m security.”

In marketing materials and contract bids, G4S sells itself as the world's premier security company – a private army of experienced guards ready and able to protect people at a fraction of the cost of police.

That pitch has been effective. The London-based company entered the U.S. marketplace in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks and, by its height in 2014, had grown into the third largest private employer in the world, behind only Walmart and Foxconn. Its American operation, headquartered in Jupiter, Florida, has collected billions of dollars in private and public contracts to guard hospitals and banks, airports and gated communities. G4S guards drive prisoner transport vans and stand watch over sports fans, college students and grocery shoppers.

But the company’s efforts to penetrate the U.S. market with low-cost protection have repeatedly come at the expense of its own hiring and training standards. G4S has sometimes given power, authority and weapons to individuals who represent the very threat they are meant to guard against.

Documents show the company's American subsidiaries have hired or retained at least 300 employees with questionable records, including criminal convictions, allegations of violence and prior law enforcement careers that ended in disgrace. Some went on to rape, assault, or shoot people – including while on duty.

USA TODAY and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel spent more than a year investigating G4S, a global security empire that is largely unknown to the American public even though its guards are omnipresent in daily life.

Visual story: A year of violence at G4S, in charts

Reporters reviewed thousands of police reports, court filings and internal company documents and matched guard rosters against criminal records and lists of decertified law enforcement officers. Then they interviewed current and former G4S employees around the country, as well as victims of the violence.

The reporting revealed a pattern of questionable hires often driven by low wages, high turnover and pressure to sign new contracts and bring on enough guards to meet the requirements. Some employees who raised safety concerns were ignored, punished or threatened while G4S executives cast the most serious incidents as aberrations.

The company’s most infamous guard, Omar Mateen, thrust G4S into the American spotlight after he gunned down 49 people and wounded 53 more in 2016 at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub. Reports showed G4S didn't consider Mateen dangerous despite warning signs, and Florida officials fined the company for hundreds of faulty psychological records, including Mateen’s.

And while Mayo and Mateen represent worst-case scenarios, reporters found examples around the country of guards slipping through the cracks at G4S.

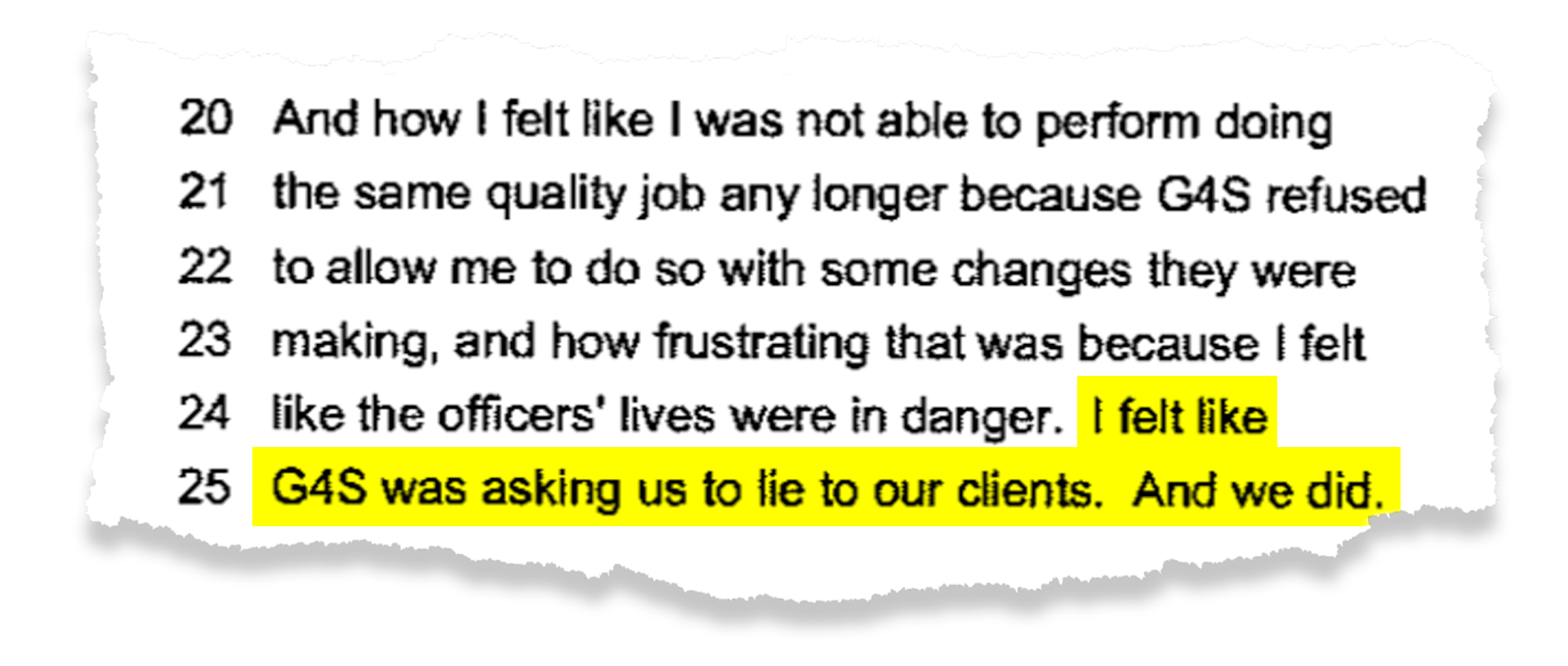

Kimberly Horton, a former operations manager in Louisiana, testified in a 2016 discrimination lawsuit she filed that G4S pushed her to quickly hire guards regardless of their qualifications.

“Fill the post. Fill the post,’” Horton recalled her supervisor instructing her, in testimony that was unrelated to her central complaint. “’If they don’t fit the criteria, put them there anyway and we will weed them out and fire them later.’”

“They just hired anybody,” she said.

G4S hired ex-cops in Arizona who had been caught lying about their relationships with underage girls and hoarding stolen department ammunition. The company armed a 25-year-old in Colorado with a documented history of mental illness who used his G4S-issued gun to shoot his family and himself. An administrator at a G4S juvenile detention center in Florida discovered guards molesting kids, police said, and then hid it from state officials because she was worried about losing the contract.

“Things are a disaster,” a G4S guard at the Radford Army Ammunition Plant in Virginia reported during a 2013 internal review of the facility. Documents from the review cite concerns after G4S slashed wages to underbid competitors and then hired untrained guards when others quit. “Why don’t they be honest about this?” another guard asked.

With little oversight from state and federal officials, G4S is primarily held accountable when clients choose to cancel contracts. But that often doesn’t happen, in part because these incidents can appear isolated.

Prosecutors offered Mayo a plea deal for his 2009 attack on the janitor. To avoid a trial, they reduced his charges from attempted rape and he pleaded guilty to misdemeanor assault.

Afterward, Citicorp, whose offices Mayo was guarding, renewed its deal with G4S.

"Citi took appropriate action,” Drew Benson, a company spokesman, said in a statement. “The third-party guard was banned from the site.”

The janitor Mayo attacked suffered brain trauma in the incident and quit her job to avoid having to work the night shift alone again.

“My life has been hell,” she told reporters from her porch earlier this year. “If you can’t trust the guards, who can you trust?”

She sued both G4S and Citicorp and accused the companies of negligence in hiring Mayo and for ignoring warning signs before he attacked her. The companies denied the allegations and eventually settled for an undisclosed amount.

In a series of written statements, G4S spokeswoman Sabrina Rios said the company enforces strict policies to prevent hiring mistakes, including training for managers and a screening process that goes above and beyond what many clients and states require.

Rios said "G4S had no way of knowing” that Mayo and other guards “would be capable of criminal acts.” She added that they all passed the company's screening procedures.

“Like all large employers,” Rios said in her statement, “there may occasionally be a very small number of employees who do not act in accordance with our procedures and policies.” She said there are limitations to what the company can and can’t find out before hiring guards.

In many cases, the problems reporters found, including domestic violence injunctions, arrests and police misconduct allegations, would not show up on a typical background check. But the information was available in public records.

Rios acknowledged that G4S cannot access all of the criminal history information it would like to get. But she said only 6% of applicants for armed positions meet the company's "stringent selection criteria."

The company is also implementing a program that would continually track employee arrests, she said.

"While it is not the norm for employees to act outside company policies, when they do those employees are disciplined, up to and including termination,” Rios said.

“Employee behavior is ultimately the responsibility of each individual who acts on his/her own free will,” she said.

Rios disputed the "characterization of 'hundreds of instances' of allegations about former G4S employees." Reporters asked whether G4S was tracking violent incidents among its guard force and whether she would share those figures, if they exist. Rios did not respond.

G4S has downsized from its 2014 peak and sold several subsidiaries plagued by reports of abuse and misconduct, including juvenile detention centers. Its two biggest competitors – Allied Universal and Securitas – have in recent years exceeded G4S’ overall employee count in the U.S.

They are teaching management how to circumvent to get business as opposed to running a legitimate business. It’s scary because the company has tentacles into every type of industry.

However, G4S is the largest security company in the world by number of employees and has earned more money in federal contracts than Allied and Securitas combined since 2005. It also arms a greater share of its U.S. employees – 11%, compared with 3% at the main competitors.

Armed G4S guards have been paid as little as $11 per hour, according to a contract in Florida reporters reviewed. Just this month, the company posted an advertisement to hire armed guards in South Carolina who would be paid a minimum of $9.25 per hour.

Supervisors have employed people without required security licenses, overlooked deficiencies on job applications, understaffed posts, and overworked guards for up to 16 hours a day, according to state inspections, county audits and testimony from employees.

Michael Hodge, a former secret service agent who is now a private security consultant and an expert witness in legal cases concerning the industry, called G4S’ organizational problems “a total breach of public trust.”

“They are teaching management how to circumvent to get business as opposed to running a legitimate business,” said Hodge, who reviewed the journalists’ findings at their request.

"It’s scary because the company has tentacles into every type of industry.”

But hiring cheaper security guards to do jobs once handled by sworn law enforcement officers has proven hard to resist, especially for governments looking to cut costs.

Police departments around California outsource jail security to G4S, which offered to pay guards up to 40% less than city employees. In May 2015, the police chief in Bell, California, asked G4S to reduce wages even more, which would save an additional $44,000 a year. The company manager explained in an email that such a pay cut would result in higher turnover and less qualified guards watching over the jail.

“We will take the lower cost," the chief emailed back.

As G4S grew in the U.S., states failed to keep it in check

G4S grew into a global force that would help reshape the private security industry by making moves the business world and investors celebrated.

In 2000, a British security company merged with a century-old night watchmen firm from Denmark to become Group 4 Falck, which later renamed itself G4S. After the merger, then-CEO Nick Buckles pushed to buy dozens of smaller firms around the world.

He expanded G4S’ footprint to more than 100 countries and took on business others wouldn’t. Guards moved cash in armored vehicles in South Africa, cleared land mines in the Middle East and provided muscle to fledgling governments in war zones.

The company entered the U.S. market in 2002 with its $570 million acquisition of The Wackenhut Corporation, a security firm founded in the 1950s by former FBI agents. It inherited Wackenhut’s lucrative government contracts to guard nuclear facilities and military bases, and salesmen fanned out to land new business.

The sales pitch – security at a discount – found a receptive audience in a post-9/11 America led by a White House pushing to make government more efficient by embracing privatization. And private businesses considered guards not just a visual deterrent to crime, but also a counter argument to litigant claims that they were negligent in protecting customers. Bank of America is now one of the company’s most well-known corporate clients. Gannett, which owns USA TODAY and the Journal Sentinel, has done business with multiple security companies, including G4S.

Buckles resigned after an investor revolt and in the fallout of the company’s most notorious contract blunder, in which it failed to deliver all of the 10,000 guards it had promised for the 2012 London Olympics. The British military had to step in.

By 2014, G4S had increased its staff worldwide from 136,000 to 620,000, about the size of South Korea’s active military. Revenue had doubled to almost $10 billion a year, according to the company's financial reports.

Today, in the U.S., G4S has field offices in 41 states and employs about 48,000 people nationwide. The company’s presence in America has been essential to its growth, even beyond the contracts it has secured. Investment disclosures show more than 40% of its backing comes from U.S. investment firms, including BlackRock, Harris Associates and Invesco.

The company has collected more than $6 billion from taxpayers through federal contracts since 2005, according to government data, and G4S has worked for the Army, Navy, Air Force, State Department, Drug Enforcement Administration and Internal Revenue Service. Immigration and Customs Enforcement currently pays G4S about $20 million annually to transport detainees in California.

Tom Conley, president and CEO of The Conley Group, a security consulting firm in Des Moines, Iowa, said G4S’ expansion into the U.S. helped drive an industrywide trend of consolidation and scale. The handful of massive corporations dominating the industry prioritize landing as many contracts as possible “when they should be focused on customers and employing people adequately prepared to handle emergencies,” Conley said.

But the patchwork of state regulatory agencies tasked with overseeing G4S operations has not forced the company to make significant adjustments, even in the wake of serious missteps. A review of state licensing records shows that agencies have done little more than issue fines that pale in comparison to the company’s growing business.

For example, in Minnesota, officials in 2010 fined G4S $250 for licensing issues. When the company’s license came up for renewal seven years later, regulators found the same problems.

The state renewed the license and issued another $250 fine.

In 2013, New York regulators proposed a $117,500 penalty against G4S for nearly 400 violations that “demonstrated untrustworthiness and/or incompetency” in complying with state regulations. The company negotiated to have the fine cut in half. It has earned at least $134 million in contracts with state and federal agencies in New York since 2005.

The largest fine a state licensing agency imposed against G4S appears to be from Florida after Mateen’s 2016 massacre at the Pulse nightclub. Mateen, who was fatally shot by police in the incident, was off duty and did not use a company weapon. G4S was not doing business with the nightclub.

After the shooting, reports revealed that Mateen had been on a terror watch list and had been questioned multiple times by the FBI. Rios, the G4S spokeswoman, said in her written statement that the FBI never informed G4S about its concerns with Mateen.

However, company officials shuffled Mateen from post to post due to problems with his co-workers and complaints from law enforcement about threatening behavior, investigations into the Pulse shooting revealed. Florida regulators also found that G4S had submitted more than 1,500 psychological questionnaires, including Mateen’s, purportedly signed by a psychologist who had stopped working with the company two years earlier. G4S has argued in court that the tests were valid even though they had the wrong evaluator’s name on them.

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, which regulates the private security industry, fined G4S $100 for each document, for a total of about $151,000.

The fine was dwarfed by at least $157 million in contracts G4S has made from Florida state agencies in the past 10 years, according to state contract data. Since the Pulse shooting, the company has won or renewed 200 contracts with the state.

“We exercise the maximum accountability allowed by state statute,” said Franco Ripple, a spokesman with the regulatory agency. He added that the agency is “looking into additional measures to enhance public safety and accountability in the industry."

When hiring guards, vice president advised: 'Think image, not qualifications’

Robert Bobo, a G4S vice president in Colorado, told his recruiters he looked for a certain type of job candidate.

To win contracts, he instructed them to “think image, not qualifications” when it came to hiring guards, according to a complaint letter one of his subordinates sent to human resources in 2016. Bobo confronted another recruiter for "hiring terrorists" because the guards were of Middle Eastern descent, according to the complaint.

On paper, Robert Leiman, 25, fit the profile Bobo described. He was white, ex-military and willing to work graveyard shifts as an armed guard at an apartment complex and various office buildings around Denver.

Leiman, however, was not the ideal candidate. He had been discharged from the Army amid questions about his mental health and after threatening to kill a fellow soldier.

On Jan. 20, 2014, Leiman and his parents argued about his erratic behavior, according to police records. He had smashed glasses, peeped on his stepsister through her bathroom window and threatened to “stomp” his stepmother. His parents told him it was time to move out of their home.

Instead, Leiman grabbed the .38 Smith & Wesson revolver G4S had issued to him. He shot his stepmother dead, shot his father in the face and then sought out his stepsister, who hid in a closet and called police.

“My stepbrother Robbie started shooting,” she whispered to the 911 operator, trying to stifle her sobs. "I’m so scared.”

Leiman never got to her. He killed himself before police arrived.

The recruiter who hired Leiman would later tell police that Leiman’s troubles in the military didn’t concern him. He said he was looking for reasons to hire guards, not disqualify them.

Bobo’s comments about image “do not reflect the view of G4S,” according to Rios, the company spokeswoman, who said Leiman passed a criminal background check and psychological screening.

Bobo, whose LinkedIn profile says he still works for G4S in a "semi-retired" capacity, did not respond to voicemails requesting an interview.

Two months before the Leiman shooting in Colorado, G4S CEO Ashley Almanza had reassured investors who voiced concerns about high-profile incidents that reflected poorly on the company's global brand.

G4S can “hit the ball out of the park for 364 days of the year,” Almanza told them during a conference call. “And on the last day of the year something goes wrong.”

But a USA TODAY/Journal Sentinel review of police and regulatory records across the nation found that, in any given year, there are frequent problems.

In 2014, the year following Almanza’s comments, the company averaged at least one incident every other day in the U.S., according to police documents, state oversight reports, court files and other public records.

Police arrested a guard in South Florida for allegedly pimping an underage girl out of the hotel he was guarding. Independent auditors in Arkansas detailed a litany of problems at a G4S-run detention facility, where kids said the staff bribed them with candy to beat each other up. At the same facility, one employee was fired for assaulting children and then rehired, only to do it again.

G4S in 2017 sold its interests in the juvenile detention center business. Most of the violence reporters cataloged came from those contracts. But incidents have occurred in a variety of settings in recent years.

In November 2016 a pregnant guard said a coworker sexually assaulted her at the hospital where they were posted in Florida, according to a report by the state inspector general, which sustained the allegation.

A G4S guard in 2017 was accused of pulling a gun during a road rage incident. Texas officials suspended another for domestic violence. He had previously been investigated for child abuse in Florida after police said he beat his stepson at least twice – once cracking his face against a doorjamb. The state declined to prosecute.

Last year, a guard in Oregon was sent to prison on child pornography charges.

In 2017 and 2018, at least 65 guards – not including juvenile detention employees – were investigated for misconduct, accused of crimes or disciplined by state regulators.

'My God. What in the world are we doing?'

G4S touts “the most rigorous pre-employment screening process in the industry” – background checks that include a review of criminal histories, references and state certifications.

But chronic turnover has left the people responsible for filling empty guard posts with little choice but to hire whoever they can get, former G4S managers said in interviews, testimony and internal company complaints.

In 2013, G4S’ security contract was up for renewal at the Radford Army Ammunition Plant in Virginia, a sprawling military manufacturing campus.

The company slashed its bid and then gutted employees’ wages and benefits, according to company emails, records from the internal investigation and interviews with two former supervisors.

Many of the existing guards quit, and those who remained said they had to work up to 18 hours on a single shift, or 100 hours a week. A security manager at BAE Systems, the defense contractor that hired G4S, wrote in a May 2013 email that the site was struggling to refill the positions.

“We still do not have a training program up and running, which is a huge concern to me,” he said in the email. “We have officers on patrol and post that do not really know what to do or the importance of their position because of lack of training.”

Instead of screening people’s employment histories, former site supervisor J.L. McKinney said in an interview, recruiters hired guards who promised they could run a mile and do pushups. The goal was “just to get the bodies in,” said McKinney, who sued G4S alleging racial discrimination and harassment. The company denied the allegations and a judge dismissed the suit in 2016.

G4S handed out guns to people who had beaten their wives and committed crimes, according to McKinney, who oversaw about 70 guards. In one case, G4S hired and armed a man who had recently left a psychiatric institution and wasn’t supposed to have a gun, he said.

“My God,” he recalled thinking. “What in the world are we doing?”

A year later, G4S sold its subsidiary that held the contract and many others with government clients. The company now brings in about 89% of its annual revenue in the U.S. from corporate clients, according to Rios' statement. McKinney still works at the site for BAE.

Similar situations have played out around the country, where G4S managers have missed or ignored applicants’ troubling histories, records show.

In at least two states, G4S hired guards for armed posts despite histories of restraining orders and arrests for domestic violence.

A G4S manager in South Carolina told state officials in 2012 that “short cuts may have been taken in the past” when the company hired at least one guard without checking for training certificates. In Washington state, G4S deployed guards without valid licenses because of “administrative staff turnover,” according to a 2014 letter from the company in a state investigation. Tennessee children’s services officials in 2016 said in agency emails the “continued instability” inside G4S had led to frequent delays in submitting juvenile detention guards’ criminal background checks to the state.

A recruiter in Florida said under oath she didn't check at least one applicant's court records. She assumed it wasn't a serious charge because he had been honorably discharged from the military.

In that state, nearly 400 guards were arrested from 2007 to 2018 either before they were hired or during their tenure with the company, according to an analysis of criminal records maintained by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and guard rosters maintained by the state licensing agency.

At least two guards had a documented history of mental illness in previous government jobs – personnel files that were a phone call or public records request away – before killing themselves in uniform with G4S guns.

The Navy gave Devin Bailey, 21, a medical discharge in 2006 after he was hospitalized with severe depression and psychosis within a week of enlisting.

Bailey’s mother called the police in Washington, D.C., a year later to have her son committed for a psychiatric evaluation. Police arrested him after he assaulted one of the officers who responded to the call. The court ordered Bailey to a mental hospital to see if he was mentally fit to stand trial.

“I need some help,” he told the intake nurse. Bailey was hearing voices and suffering from hallucinations. Doctors diagnosed him with bipolar disorder and put him on medication before discharging him. A year later, Bailey checked himself into another hospital. Doctors increased his medication.

Four months after he left the hospital, Bailey applied for a job at G4S. A background check revealed that Bailey had an active warrant for skipping a court date, but company officials did not follow up with the court or police, according to court records. The company also did not receive or ask for his military discharge records, his family said later.

The company hired Bailey in November 2008 and assigned him to guard the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Washington, D.C., on a contract with the U.S. Army. The company issued him a gun.

Bailey killed himself with it less than a month later, while he was posted in a guard shack just outside the military hospital.

His mother filed a lawsuit against the company, alleging it had been negligent in arming someone with an active warrant and a history of mental illness. A judge dismissed the case in part because corporations can’t usually be held responsible when employees die by suicide. But in his written decision, the judge made the following observation about G4S:

“Certainly, the allegations in this case raise serious questions about the diligence and care with which (G4S) performs background checks on the employees to whom it provides firearms.”

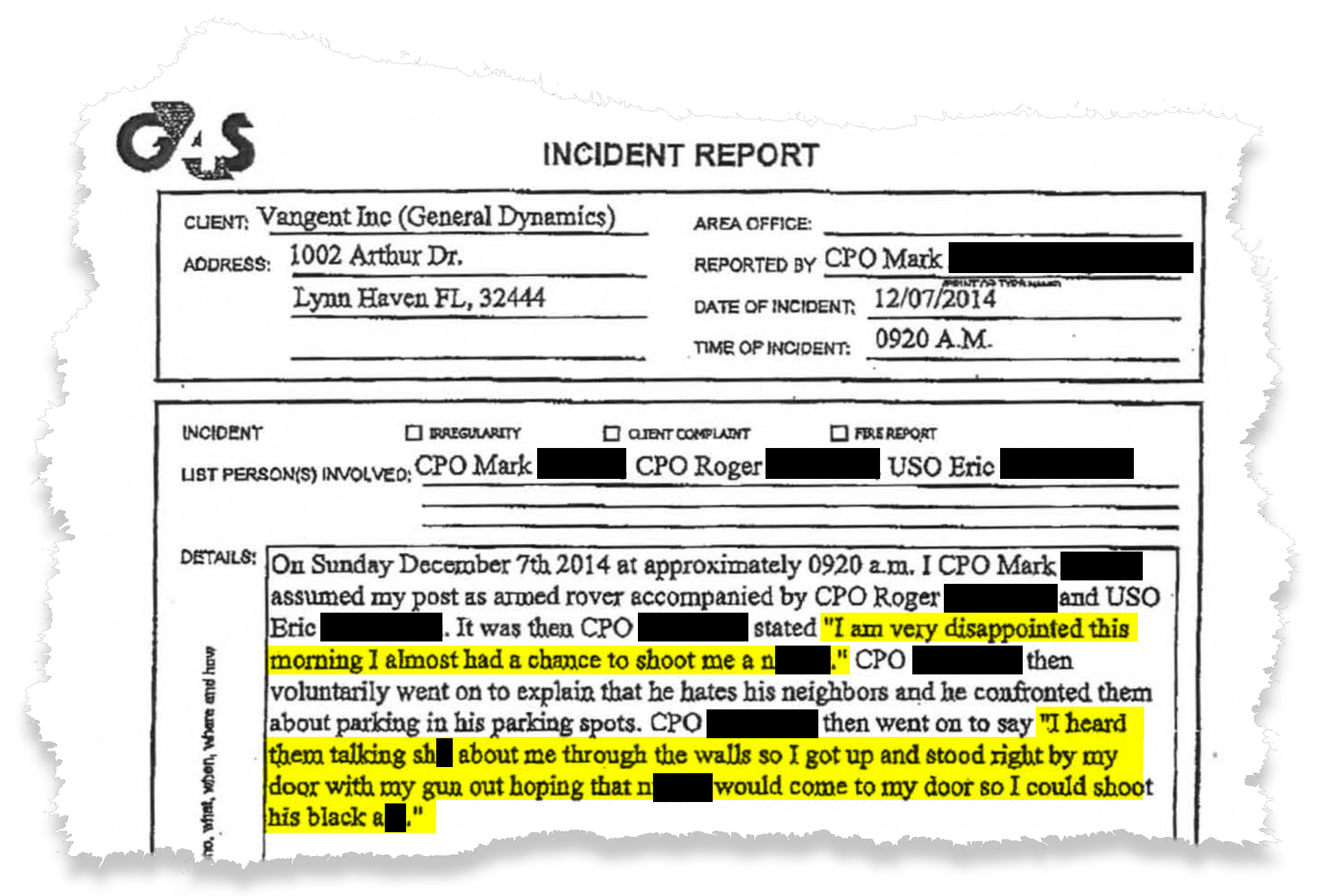

Disgraced police officers find a home at G4S

At the center of the G4S sales pitch are former police and military veterans, marketed as "the best in the security industry.”

They often are not. Since 2008, the company has employed at least 200 former police and corrections officers who had been stripped of their badges, forced to resign or were reprimanded over serious accusations, such as excessive force, sex offenses, domestic violence, and perjury, according to a USA TODAY/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel analysis of publicly available police records and G4S guard rosters.

At least three police chiefs who resigned amid internal investigations or scandals later found jobs as G4S supervisors. A small-town chief in Wisconsin was convicted of five misdemeanors and served three months in jail with work for drinking while armed and for disorderly conduct, which included propositioning officers for sex. G4S hired him.

Rios, the G4S spokeswoman, said the company is sometimes unable to obtain negative information about former law enforcement officers.

“Information on individuals who leave law enforcement as a result of decertification or resignations amid internal affairs investigations may not be made available to external companies who verify employment,” Rios said in her statement.

In some cases, G4S hired disgraced officers to do jobs similar to those they performed in their law enforcement careers.

The Pasco County Sheriff’s Office in Florida investigated Andrey Izrailov, one of its deputies, more than 20 times, internal affairs records show.

Although he was never charged with a crime, Izrailov ultimately resigned in 2009 amid an internal investigation into allegations he had delayed responding to police calls and falsified paperwork to make it look like he had spent more time at scenes.

In 2013, G4S hired him to drive a transport van under a new contract with the sheriff’s office in Pinellas County, which neighbors Pasco. G4S didn't have time to fully train new hires, so the company gave Izrailov and others a condensed version of the training, according to sheriff's office internal affairs records.

Two months into the job, Izrailov picked up two intoxicated men. One of them, Leonard Lanni, had tried to start a bar fight. The other, Thomas Morrow, was in protective custody. Izrailov had received incomplete and conflicting instructions about whether to restrain and separate prisoners in the van, so he kept them in the back together and unbuckled.

Lanni attacked Morrow, 59, on the way to the jail. Morrow, who was handcuffed, screamed for help, but Izrailov kept driving, internal affairs records show. By the time Izrailov pulled into a parking lot and asked two sheriff’s deputies for help, Morrow had stopped screaming.

He died from his injuries two months later, and Lanni was ultimately convicted of murder.

The internal investigation absolved Izrailov of wrongdoing. G4S still had not finalized its training program by the time the investigation was completed, the report noted.

Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri defended G4S after Morrow’s murder. He has since renewed the $4.8 million contract with the company, which had hired his former chief deputy to lead a sales team targeting law enforcement contracts. Gualtieri declined a request for comment.

Izrailov, who has since been hired by another local police department as a part-time code compliance officer, did not respond to voicemails.

Morrow’s widow, Sharon, blamed G4S and the sheriff who chose “to save a buck” by hiring “these incompetent people who should never be involved in law enforcement.”

“Putting people’s lives at risk,” she said, “that’s exactly what he did by hiring G4S.”

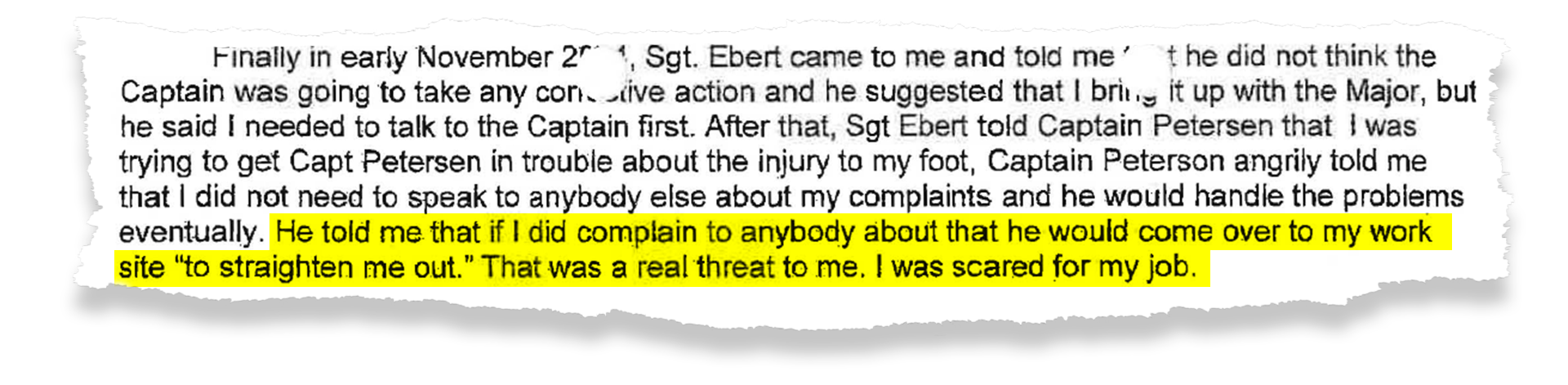

Employees punished or fired for airing complaints

G4S has retaliated against internal whistleblowers to keep problems from surfacing, according to interviews, internal complaints and multiple lawsuits filed as recently as last year.

Employees said managers have threatened them so they would not use the company complaint hotline. One guard was put on administrative leave after telling police a coworker had assaulted her.

That complaint hotline for "improper, dishonest or unethical conduct" logged more than 500 internal allegations of wrongdoing in 2018, according to the G4S' own count.

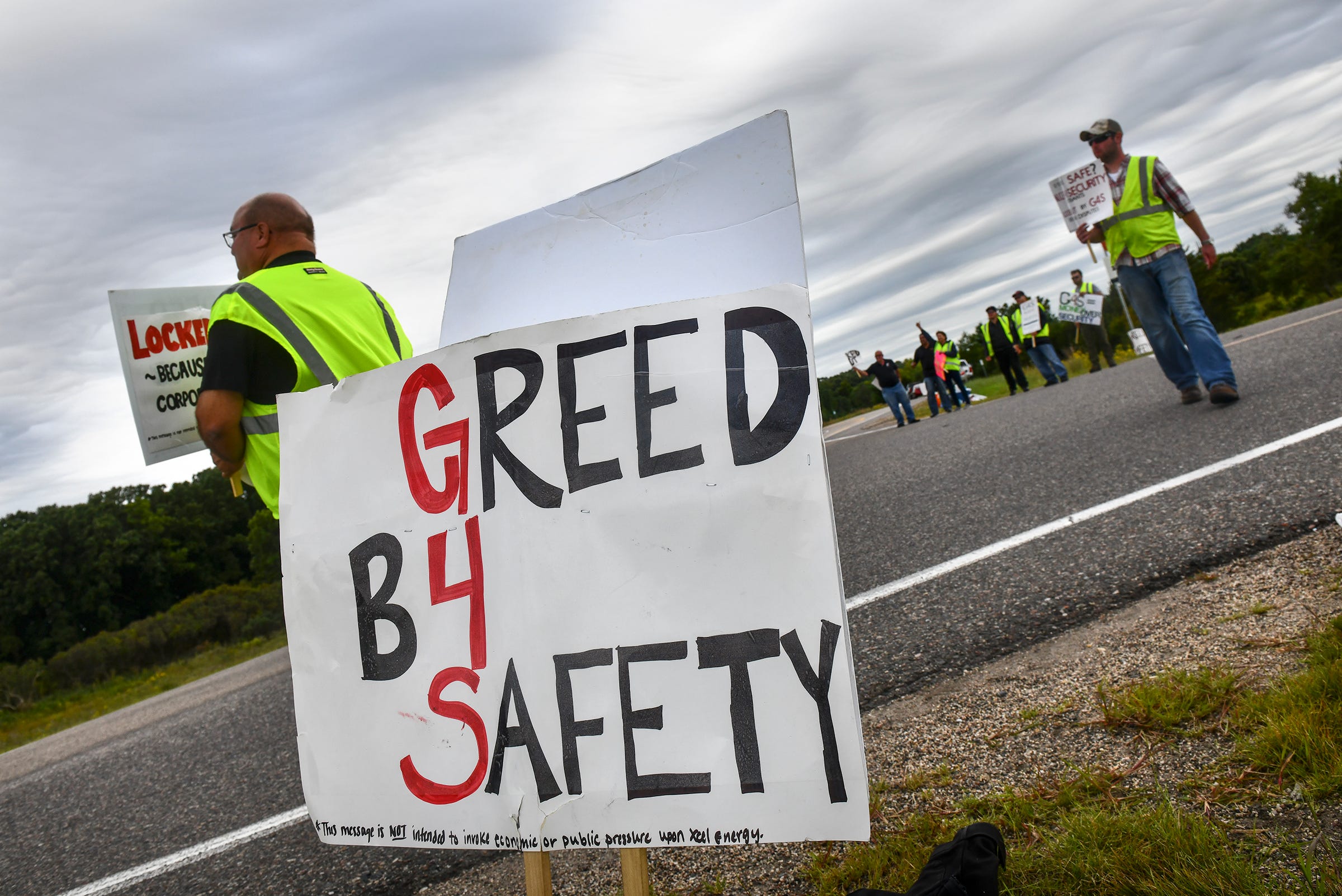

At the Prairie Island nuclear plant in Minnesota – which has two reactors that power electricity in much of the Midwest – equipment malfunctioned, weapons disappeared, and guards fell asleep on duty, according to a lawsuit filed by one of the guards there.

Joseph Schumann testified that he reported these concerns to his bosses at G4S, which held the contract to keep the plant secure, but they took days or even weeks to address the issues.

And when Schumann, who was born in Thailand, reported his co-workers for calling him racial slurs, he said supervisors did nothing.

Schumann took some of his concerns to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 2013. Two weeks after officials there decided to open an investigation, G4S fired Schumann.

“I reported it, and I don't think G4S wanted to know,” he testified as part of a racial discrimination lawsuit that the company ultimately settled.

Rios said in her statement that the company’s “records show our nuclear sites to be some of our most highly performing sites.” She added that G4S fired Schumann “for failing to report another officer sleeping in a timely manner.”

Rios also said the company takes internal complaints seriously and encourages employees to report any problems they see.

Other employees documented similar allegations of intimidation, retribution or blatant acts of racism, sexual harassment and violence.

Co-workers have called African American employees racial slurs and displayed racist imagery, including a noose, according to internal company complaints.

An African American guard in Oklahoma said she was promoted to supervisor to fire other black employees under false pretenses, protecting the company from discrimination lawsuits. She was later fired.

An employee in Tennessee said she was fired after reporting that a colleague had grabbed her by the ponytail and bent her over an office table in front of a group of co-workers.

State investigators in Florida substantiated more than 1,500 allegations against staff members at G4S-run juvenile detention centers between 2007 and 2017, including abuse, neglect and sexual violence, according to state data.

That number doesn’t include what company administrators tried to keep secret.

At one facility, a G4S administrator who discovered that two guards had been molesting kids let them stay on the job and then hid the crimes from state officials, according to police records. One of the guards later sexually assaulted another teenager, detectives found.

Employees at the facility had also threatened kids with longer sentences to prevent them from reporting physical abuse, the victims told police. One boy said a staff member led him to a tool shed after he tried reporting medical neglect. Four other inmates were waiting. They turned off the light and then pummeled him.

In June 2015, a grand jury in Polk County called the facility a “disgrace” that “should cease to exist.”

“G4S internal policies discourage contacting law enforcement when crimes occur at their facilities,” the grand jury wrote. G4S ran the operation for two more years before selling its youth services subsidiary in April 2017.

How concerned are they with the children here? They’re over there looking at bottom line numbers and profit.

Four months later, Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd arrested three of the former G4S administrators for tampering with evidence and failing to report child abuse. In a statement at the time, Judd called the coverup an “ongoing pernicious conspiracy of silence" to save the $40.1 million contract.

One of the administrators died earlier this year before the court case concluded. The two others saw their charges dropped or reduced in deals with prosecutors.

“How concerned are they with the children here?” Judd said of G4S executives in a recent interview. “They’re over there looking at bottom line numbers and profit."

But Judd currently pays the company $2.75 million to guard courthouses and transport inmates to county jails. He said he had no hesitation about contracting with G4S, despite what he discovered while investigating the company two years ago. He can trust the local management because G4S employs a number of his former deputies, he said.

“They’re a massive operation,” Judd said. “I control the contract and everyone who’s on it."

More in this series

- Security giant G4S has lost hundreds of guns. Here’s where we found them

- Inside the U.S. military's raid against its own security guards that left dozens of Afghan children dead

- Reporting on a deadly airstrike in Afghanistan

- Augmented reality: One security company, three warlords and dozens of dead Afghan children

- A year of violence by guards at the world's largest security company

- The Pulse nightclub shooting and other G4S scandals

- Five things you should know about guns lost by G4S, the largest security company in the world

- Five takeaways from our investigation into the world's largest private security company

- G4S guards in Florida: lost guns, sex sting arrests and fired cops